3 Speed Training Fallacies to Avoid

By Travis Hansen / Author, The Speed Training Encyclopedia

In this article we will explore and identify three of the most common speed training myths on the market today. It’s quite possible to perhaps argue the three that I’m going to select, however, these three are, in my opinion, are the most common of all the potential myths out there.

And these three are: “Flexibility training for increased speed, size makes you slow, and technique as the most important factor for greater running speed.

Hopefully, after I provide some sound science and evidence to support each of these myths, you will have a newfound perspective on each of these, or it will just confirm what you already knew.

#1-FLEXIBILITY TRAINING FOR INCREASED SPEED

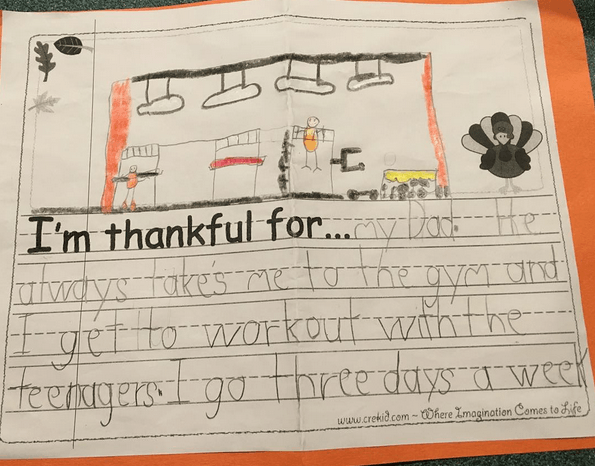

Just about every first time athlete that I train, or parent or coach I talk to will be sure to make sure that this type of training is practiced regularly in their athlete’s program, above everything else. I will never deny that flexibility and mobility work is integral to the athletic development process, however, it is a definitive secondary measure if the objective is to get faster, and here is why.

First, have you ever witnessed very many superbly fast athletes who were extremely flexible and lax? Ya me either. Of course there are exceptions to every rule, but it’s rare to see this type of person. In fact, every single one of my fastest male and female athletes possessed a moderate degree of muscle-tendon stiffness.

A key physical trait that enables more efficient and effective movement. I like to use the blood vessel analogy when attempting to convey this message. What happens when our fight or flight response is activated? Our blood vessels tighten and constrict which allows blood and energy to travel to target sites in the body faster to meet the task at hand. Our muscles work the same way in motion.

When our muscles contract, the tissues remain stiff which enables energy to be transferred through our limbs much better and efficiently then if we were loose. Just think of a marionette when attempting to understand this concept, and you will realize that we need to be somewhat tight and stiff to be great movers.

The notion of having great flexibility and mobility, especially throughout the lower extremities may be well intended, but the reality is that the act of sprinting and other speed based training skills does not challenge our “Limits of Flexibility”, or the lower body muscles and joints full range of motion.

Not even close. I’ve seen some very deficient athletes in terms of flexibility and mobility over the years, but none of them were so inadequate that they were incapable of sprinting. So why do we suggest athletes to do so much of it? I don’t know.

If you are already more than flexible enough to sprint, then more of it is not going to do anything for you in the speed development process. But don’t just take my word. Research and lots of real world evidence supports this notion as well. In one particular study, a six week protocol of static stretching for the hamstrings did not improve sprint performance.

Another reason why stretching does not improve speed is due to a kinesiological principle known as “The Length-Tension Relationship” of our muscles. Basically, you can view this feature as a stretch to strength ratio. For instance, if we stretch a muscle too much it loses power and force production capabilities, and vice versa. There is a “moderate” degree of stretch required by our muscles and tendons in order to elicit a powerful movement response from the body. The body searches and activates this naturally in athletic movement patterns. Sprinting, vertical jumping, cutting, and landing all involve moderate amount of motion. If the motion was to elaborate and large then power would decline and its because of this phenomenon.

Another reason why I disfavor high amounts of stretching is because it induces relaxation of the body. This is the opposite state we want our body to be in when lifting heavy weight and attempting to run fast. We want a heavily excited and stimulated Central Nervous System, prior to these activities, otherwise performance will be limited. There was one study that showed decreased neural drive to the muscles for up 24 hours after a static stretching series was performed.

Now I do think stretching is important when developing speed, it’s just not for the reasons that so many are fond of.

I think in sport and competition it is important to have the potential to move through a larger range of motion, but not more than you have too. This can help prevent injury in unpredictable and unusual movement situations that sometimes occur in athletics.

There are also a number of other critical functions that stretching is responsible for that I will list below.

I think where it can shine the most is in the recovery-regeneration process.

#1-Helps activate the Parasympathetic Nervous System

#2-Promotes Relaxation-reduces Sympathetic tone

#3-Removes metabolic waste products

#4-Facilitates recovery

#5-Increases sensitivity to androgens

#6-Improves flexibility and mobility

#7-Prevents or treats injury

#8-Repairs scar tissue

As far as programming is concerned, studies show strong improvements in flexibility-mobility at a frequency of 2-3 x per week, where the stretches are performed on non-training days. 3-5 sets of 10-60 second holds at a point of tension or a sticking point works great.

SIZE MAKES YOU SLOW

Assuming that increased mass automatically makes you slow because it increases gravity and requires more effort to move is far too simplistic.

The fortunate scientific fact is that increased cross section area or muscle size, especially at target and specific areas of the lower body can result in greater running speed!

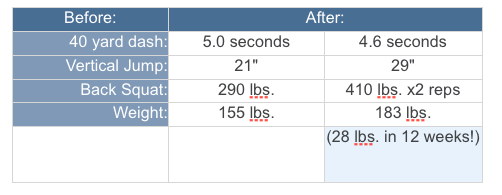

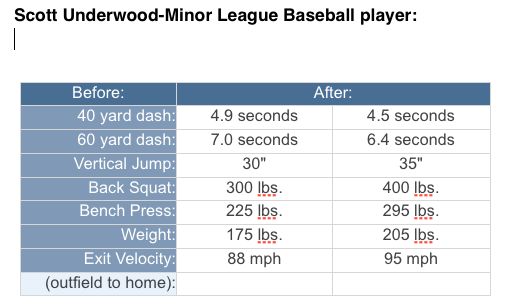

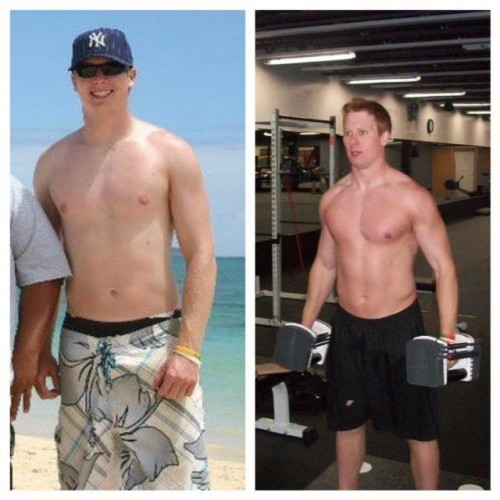

A famous study was conducted on a series of male and female runners ranging from various track and field distances (100m-10000m). 3 The consensus was that the biggest runners were also the fastest! 3 And there is more than enough real world evidence to refute this myth as well. Look no further than an NFL Combine. Enough said. And to put the icing on the cake; here is two of my elite athletes along with their results from our speed training program:

Nolan Wilcock-College Student / Ex-Athlete

Testament that speed gains can be developed when bulking up.

They are two of many that have gone through our system.

The 2 primary reasons why increased local muscle mass can improve speed is due to the fact, that the increased mass can raise strength and power potential, along with enhancing our muscle’s unique supportive action referred to as: “The Myotatic Stretch Reflex.”

Simply put, the faster and harder we can pre-stretch a muscle before we move and contract it, the more energy we can store in our tendons and the greater our muscle recruitment becomes. Both of which result in greater power and speed.

The extra mass allows us to stretch our muscles faster and harder since we gain strength and power with more size.

TECHNIQUE IS THE PRIMARY FACTOR FOR SPEED

If you were to talk to many track and field coaches, or athletic development coaches around the country, I’m sure that several would state that sprinting technique is the most critical factor for success. But is it?

Although there has been research that has shown that technical proficiency is a necessary precursor for speed, the precursor for technique is always power.

Two studies were conducted on the fastest African American sprinter (Usain Bolt), as well as the fastest caucasian sprinter (Christophe Lemaitre). 4 5

The studies verified that these two sprinters were so successful, due to the fact that they exhibited such high levels of power (strength x speed) during their sprints relative to their bodyweight.

Meaning that they put more force into the running surface faster than anyone of their decent.

This should be reason enough to start implementing direct methods of power training right away, if your goal is to get faster!

You might be curious as to what constitutes power training, so I will provide you a few examples right now.

Weightlifting (aka Olympic lifting) variations from the hang, standing vertical jumps, running vertical jumps, broad jumps, jump squats, speed squats, and 20 and 40 yard dashes are all some of the many examples of power training.

The take home message should be that technique is critical to success, however, if you do not have a foundation of power then you will go nowhere and you will be unable to properly demonstrate all of the various techniques (forefoot dominance, leg stiffness, arm and leg drive, etc.) to increase your speed.

What many fail to see is that it’s the power that is creating the technique rather than the other way around.

For example, if you need fast and strong arm and leg drive, but you lack power skill then your limbs will not operate very well.

Forefoot dominance, or running on the front of your foot is essential to speed, but if you lack power you will not be explosive enough to sustain balance over your base of support and run faster.

There are several more examples like these that can be observed.

Lastly, you can take a youth athlete who runs pretty, and a pro athlete who does not, but we both know the pro will dominate and mask any potential deficiency he has in technique and blow by the kid because he is so much stronger and powerful than the adolescent.

Train power first, and you will be amazed at how much your technique starts to clean up and how much better you’ll look when you run.

_________________

Got questions / comments on speed training? Drop your comments below and Travis and I will answer.

I've had the opportunity to thoroughly review Travis's Speed Training Encyclopedia and I dig it BIG time. Highly recommended for other Coaches & Parents looking to obtain easy to understand and results driven speed training workouts and techniques.

Live The Code

--Z--

For more in depth information on how to develop explosive speed and power, check out “The Speed Encyclopedia” HERE

SCIENTIFIC REFERENCES:

1-Jones D, Gibson M, and McBride JM. Sprint and Vertical jump performance are not affected by six weeks of static hamstring stretching. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 22: 25‐31, 2008.

2- Haddad M, Dridi A, Moktar C, Chauouachi A, Wong DP, Behm D, and Chamari K. Static stretching can impexplosive performance for at least 24 hours. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2013.

3-

Weyand P, Davis A. Running performance has a structural basis. Journal of Experimental

Biology 208: 2625‐2631, 2005.

4-

Beneke R, Taylor M. What gives Bolt the edge‐A.V. Hill knew it already! Journal of Biomechanics 43: 2241‐2243, 2010.24

5-

Morin JB, Bourdin M, Edouard P, Peyrot N, Samozino P, and Lacour JR.

Mechanical determinants of 100m sprint running performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology 112: 3921‐3930, 2012.

7 Responses

One of the best articles yet! Thanks, Z!

Thnx, Frank! Solidifies the fact that we gotta be strong to be explosive!

Great article Zach.It makes sense.

Hi Zach,

I’m just getting into sprinting, I’m attempting to qualify for a team in the 60m, any tips for increasing speed for someone who doesn’t have much space to run? Currently, there is a ton of snow outside and I don’t have access to an indoor track. I have a bit of a oly lifting background and some crossfit. I have a terrible vert too, only 26″ but roughly a 120kg power clean @ 180lbs.

Thanks!

Lucas GREAT question, brotha.

If you can’t sprint outdoors, you can focus on strength and power

Deadlifts

Cleans

Dumbbell Snatches

Box Jumps

Kettlebell Swings

Squats / Box Squats

This sounds crazy, but get to a parking deck where there is NO snow and work your starts and work tempo runs

I’ll have Travis add his comments from here to help you get to the next level

From my standpoint, you need to keep getting stronger and more explosive via resistance training, jumping and throwing of implements.

Have you followed Travis’s program here?

That would be THE ticket, brotha!

Hey Lucas,

First off, good luck! Secondly, I would have to agree with most of Zach’s insight into your situation as making the most out of the situation. Rather than powerclean which has not been shown to be very effective in increasing sprinting speed, go ahead and opt for the hang clean or snatch. Much more specific to the activity, more speed based, shorter ground contact time, etc.

Lastly, although you certainly can improve several deficiencies without a running track, it’s imperative that you find somewhere to run since there are so many essential changes that occur on the cellular level with direct speed work and you will never be your best without it. Hope that helps.

Sorry Zach and Lucas. I agree with all of Zach’s comments! I just was not sure if he meant power or hang clean variations. Just wanted to clarify that. All of the aforementioned drills have a specific purpose and place in a speed oriented training system.